The Pacific Solution - Disegno Journal

In August 2001, the Australian government was reeling. In the run up to the November federal elections, polls had revealed a slim lead for the opposition Labour candidates and John Howard, the prime minister and leader of the centre-right Liberal party, became desperate. As if on cue, on 24 August, an Indonesian fishing boat overloaded with people seeking asylum – the Palapa 1 – became stranded in the Indian Ocean, feeding concerns over border protection. The situation worsened following the September 11 attacks and the climate of fear and suspicion that spread throughout the west. Then, on 6 October, another boat, designated SIEV 4 (Suspected Irregular Entry Vehicle 4), appeared close to Australian waters. The Australian navy claimed the passengers on this ship were throwing children overboard to force passage to Australia. Howard had the ammunition he needed and hastily drafted a series of amendments to migration laws: strict punishment for those arriving by sea, retroactive immunity for the government’s actions and automatic mandatory detention in offshore camps. The Pacific Solution was enacted.

While often misunderstood as the product of a single Australian government, the Pacific Solution – the nation’s policy of transporting asylum seekers to detention centres on island nations – was in fact the culmination of a series of increasingly restrictive policies by successive Australian governments that can be understood as a spatial politics of refusal. Australia was founded on refusal. It began with the hostile arrival of the British in 1788 and the negation of 50,000 years of Aboriginal history. This culture of silencing the narratives of subjected groups continued in the 19th century, this time focused on new labourers arriving from China during the gold rush. Subterfuge and innuendo gave way to overt racism in 1901 with the vote for federation and the implementation of the White Australia Policy, restricting immigration to those who could pass arbitrary language examinations. Australia’s progress has always been coupled with abject refusal. Understanding the various stages by which this came to fruition in the Pacific Solution is essential to an appreciation of its current reality.

Deep in the desert north of Adelaide in southern Australia is Woomera Village, a site established in 1947 as part of the Anglo-Australian Joint Project, a combined defence initiative of the Australian and British governments to research long-range weaponry. The site served as a hidden outpost for the Western Bloc’s war apparatus and featured two essential characteristics required in the growing Cold War and Space Race: remoteness and scale. From 1947 to 1980, Woomera Village evolved into a vast weapons testing facility and defence outpost known as the Woomera Rocket Range. At the height of its operation it encapsulated more than 200,000sqkm, an area nearly the size of Great Britain. This country within a country was restricted land. Through the decades this area has also been called the Woomera Test Facility and the Long Range Weapons Establishment. Today, it is known as the RAAF Woomera Test Range. The site’s role has changed as often as its name. It has hosted scores of secret programmes, such as the United States Air Force’s Nurrungar and NASA’s Deep Space Station 41. Nurrungar, named after the Aboriginal word for “listen”, brought thousands of people to Woomera to monitor Russian missile launches and conduct surveillance using emerging space technologies. Deep Space Station 41, also known as the Island Lagoon Tracking Station, was integral for the NASA Gemini and Apollo programmes and played a critical role in the first moon landing. As the Cold War subsided, these facilities were dismantled, the equipment packed and the compound temporarily mothballed. The restrictions, however, remained.

In the 1990s, modifications to migration policy created mandatory detention for all people that the government decided had entered the country illegally and opened the door to indefinite detention. The existing detention facilities quickly reached capacity, however, and in 1999 parts of the vast Woomera Rocket Range were transformed into the Woomera Immigration Reception and Processing Centre, a 400-person detention facility that soon housed more than 1,500 people seeking asylum. Despite its scale and importance, Woomera remained a closed city: a vast island in the centre of a presumably empty bush. Yet the place’s geographical exile was tested in 2000 with a series of well-publicised riots, protests, jailbreaks and civil disobedience. Hundreds of Australian protesters crashed the gates of Woomera, their collective patience for the mainland territorial detention facilities waning.

The next stage in the development of the Pacific Solution came in August 2001, when the aforementioned Palapa 1 foundered off the northern coast of Christmas Island, more than 1,500km from the mainland. The passengers were predominantly Afghan refugees and their goal was Australia, but the boat was overloaded and in peril. A call by the Rescue Coordination Centre Australia was answered by Arne Rinnan, master of the Norwegian freighter MV Tampa. Rinnan set an interception course to the sinking boat. Howard, however, had no patience for these “unauthorised boat arrivals”. Australian policy was disproportionately harsh to those arriving by boat and any tolerance here would be a show of political weakness that Howard could not survive. The government denied responsibility for the people and directed Rinnan to turn his ship towards Indonesia. Rinnan refused and a standoff began.

After several days, the conditions on the deck of the Tampa worsened. On 29 August, Rinnan disobeyed orders from the Australian government and entered the territorial sea of Australia. His destination was Christmas Island. The Palapa 1 found itself in the centre of a heated political battle around migration policy, given that Christmas Island was an external territory of the Commonwealth of Australia and a part of the Australian migration zone, exclusive economic zone, and Australian territorial waters. Landing there was the equivalent of docking in Sydney Harbour – the passengers could register as refugees and their cases would be heard in Australia.

In response, the Howard government ordered that the ship be boarded by Australian Special Air Service Regiment officers. That same day Howard attempted to pass the Border Protection Bill 2001. The bill stated that if a ship enters Australian territorial waters “an ‘officer’ may detain the ship and take it or cause it to be taken, including by reasonable means or force, outside the territorial sea”. 1 The bill easily passed in the House of Representatives, before being defeated in the Senate. But the legislation did not die. Instead of a single new piece of migration legislation, the Howard government chose to repackage the Border Protection Bill 2001 into a series of separate amendments to the Migration Act 1958. This 1958 act was the replacement for the highly restrictive and racist Immigration Restriction Act 1901 – the basis for the White Australia Policy. On 27 September 2001, the amendments to the Migration Act 1958 passed and in total became the Pacific Solution.

Included in the package was the Migration Amendment (Excision from Migration Zone) Act 2001. This legislation excised thousands of Australian island territories from the official Australian migration zone, cutting off an ethical point of asylum and establishing the precedent for further excising in the future. Christmas Island was one of the newly excised islands, but it remained within Australia’s territorial waters and part of Australia’s exclusive economic zone. It meant that Christmas Island was still Australia, but also not – a crucial designation. Under earlier legislation, people who arrived in the Australian migration zone without a valid visa were subject to mandatory detention in an Australian facility. Excising Christmas Island and other territories from the migration zone, however, meant that this requirement of territorial detention could be circumvented. Landing on Christmas Island no longer guaranteed due process in the Australian courts. “Illegal maritime arrivals” were now sent directly to offshore detention facilities and were subject to the laws and processes of other countries.

This surrender of space was not complete however. In 2013, the Labour government under Prime Minister Julia Gillard took the extraordinary step of excising the entirety of the Australian mainland from the migration zone, meaning that all Australian territory is now excised from its own migration zone. This radical step was lauded by the conservative opposition and closed the final loophole in the move towards offshore detention. Now, no matter where a person seeking asylum lands in Australia, they will be immediately deported to an offshore facility for mandatory, and possibly indefinite, detention. This downward spiral of refusal has created a country that, despite its significant physical size (roughly equivalent to the 48 contiguous US states) and its relatively small population of 23 million, is now effectively invisible to people seeking asylum arriving by boat.

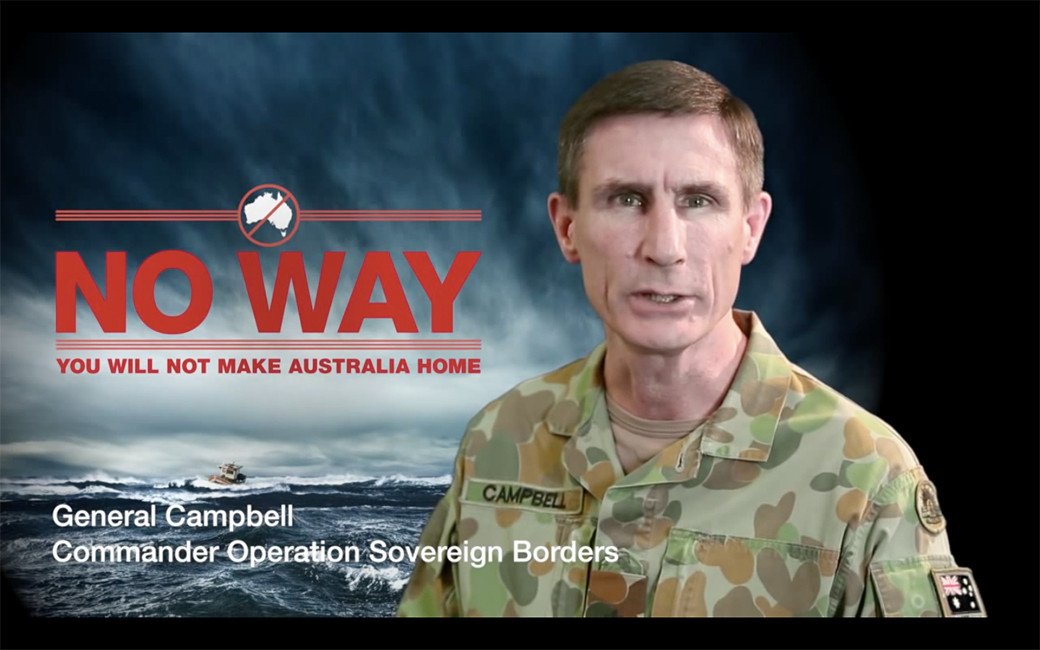

The Pacific Solution ensured that there was only one destination for people seeking asylum: offshore. The government’s policy seems to be based on the idea that it is acceptable for one group of people to suffer if it potentially deters future groups from attempting to migrate to Australia. The conservative government of Prime Minister Tony Abbott2 swept to power in 2013 with a campaign based on “stopping the boats”. The details of his policy were never articulated during the campaign and the candidate displayed wilful disregard to any journalist who dared to ask. However, once elected, the new government wasted no time in setting the tone. Within months, the Abbott government launched the anti-immigration video campaign No Way, featuring the newly appointed Commander of Operation Sovereign Borders, Lieutenant General Angus John Campbell. Dressed inexplicably in jungle fatigues, Campbell looks squarely into the camera and tells people potentially seeking asylum that there is absolutely “No way you will call Australia home.”

Despite the ridiculous appearance of the videos, Lieutenant General Campbell’s words were not idle threats. Armed with the original Pacific Solution laws and the expanded protocols defined in Abbott’s Operation Sovereign Borders, the military could now intercept a boat anywhere within Australian territorial waters, board it and forcibly remove it to international waters without fear of legal action or reprisals. Further, the Abbott government announced in 2013 that it would no longer officially report the number of turnbacks – boats removed from Australian waters. The government boasted that reported incidents of successful boat arrivals plummeted from 301 in 2013-14 to 1 in 2014-15. The actual number of turnbacks will never be known – government figures are conspicuously minimal – but accounts of injury and death from turnbacks are accumulating. The murkiness of the “stop the boats” campaign translated into a conspicuous opacity in the reporting of data.

The Nauru Regional Processing Centre, on the tiny Pacific island nation of Nauru, was established in September 2001, only weeks after the Tampa Affair. Manus Regional Processing Centre in Papua New Guinea followed in October. These new offshore detention facilities literally distanced Australians from their country’s handling of those seeking asylum. Further, their creation established an insurmountable maritime barrier between the asylum-seeker and Australia. The facilities are opaque and travel to Nauru or Manus is extremely difficult. Each year the number of visas granted drops and the non-refundable cost of the application multiplies, such that humanitarian observation has become nearly impossible. The Guardian’s recent publication of the Nauru Files3 exposed the horrific realities of the daily lives of detainees under the Pacific Solution. The thousands of pages of incident reports chronicle abuse, self-harm and assaults on detainees. The islands of Nauru and Manus have become non-places in Australia’s expanding zone of refusal, while the nation’s spatial politics has reached a pinnacle in its treatment of offshore detainees. Such people are subjected to indefinite detention and are never given the possibility of settlement in Australia. If they happen to be successful in making a case for refugee status, their choices are few. If they fail, their only option is to be returned to their country of origin, the place they risked their life to escape. Their presence in the camps is hardly recognised by the government; the ability to discern the status or welfare of the detainees is nearly impossible; and the government’s response to any criticism is to state that the boats have stopped.

In April 2016, the Papua New Guinea Supreme Court ruled that the detention of people on Manus Island was unconstitutional and ordered the governments of Australia and Papua New Guinea to make arrangements for the dissolution of the camps. In October, Amnesty International issued a report titled ‘Island of Despair: Australia’s “Processing” of Refugees on Nauru’4, which describes living conditions in Nauru that are tantamount to torture, including multiple accounts of attempted suicide and self-harm, and despair due to the lack of transparency regarding the applications for asylum. In a recent report card, the UN instructed Nauru to immediately investigate the welfare of children in the detention facility and criticised the access restrictions for media and watchdog groups.

The governments of Australia and Nauru have created an impenetrable space of deniability. The civil disobedience and presence of the protestors in Woomera in the early 2000s seems almost quaint when considering the impossibility of ever having first-hand knowledge of the conditions offshore. The Australian government’s policies towards people seeking asylum has devolved to the point that the process from identification to detainment is so hidden from view, so remote, that the average Australian cannot begin to imagine themselves in the same scenario. It is not a tangible wall on the US/Mexico border – it is a maritime expanse, indeterminate and impassable.

- Originally published in the Winter 2017 issue of Disegno Magazine

Border Protection Bill 2001, Parliament of Australia, accessed 26 March 2017, Link ↩

If you’re keeping score, there were five changes in prime minister and three changes of government between 2007 and 2015. ↩

The Nauru Files, The Guardian, accessed 26 March 2017, Link ↩

Australia: Island of Despair: Australia’s “Processing” of Refugees On Nauru 2016, Amnesty International, accessed 26 March 2017, Link ↩